Source: The Economist

Ten years ago, developing economies were catching up with developed ones remarkably quickly. It was an aberration

Sep 13th 2014 | From the print edition

NOWHERE are the consequences of different rates of growth clearer than on a trip up the Pearl River Delta in southern China. At the river’s mouth sits Hong Kong, a city in which average living standards exceed those in most rich European countries. Travel farther north and you pass the container ports of Shenzhen, behind which new skyscrapers tower over a sprawling melange of housing and factories. Since its establishment as a special economic zone in 1980, Shenzhen’s economy has grown at a frenetic pace, and incomes there are now just over half of those in Hong Kong, which is similar to what you would see in southern and central Europe.

Farther north and west sits Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong province, with its newly constructed motorways and tower blocks among the rice paddies. Average incomes in Guangdong are just a quarter of those in Hong Kong, equivalent to Algeria or Costa Rica. Finally, toward the western edge of the watershed, the tributaries reach across Guangxi into Yunnan—provinces where the people have yet to get into the flow of China’s voyage of development. Incomes there are but a tenth of those in Hong Kong, on a par with those in Angola or the Republic of the Congo.

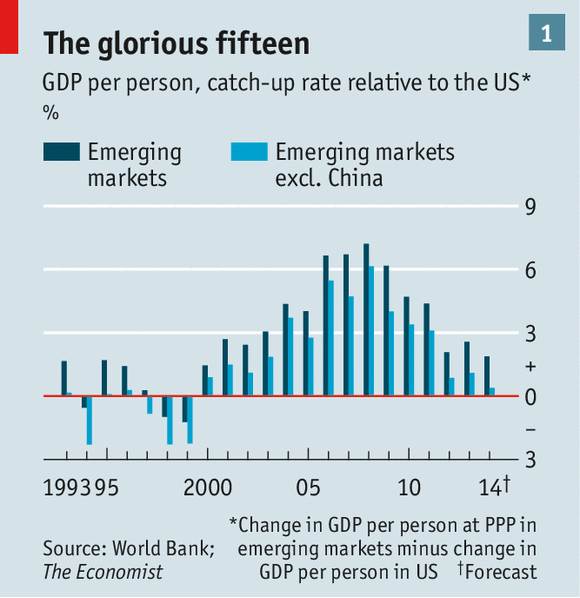

Over the past 15 years the currents that take people from such hinterlands of poverty to the broad open reaches of wealth have been flowing at an unprecedented rate. When adjusted for living costs, output per person in the emerging world almost doubled between 2000 and 2009; the average annual rate of growth over that decade was 7.6%, 4.5 percentage points higher than the rate seen in rich countries (see chart 1). As a result of that difference the gap between the developed and developing worlds narrowed quickly.

This burst of growth struck an extraordinary blow against deprivation. The share of the developing world’s population living on less than $1.25 a day (the international definition of poverty) has fallen from 30% in 2000 to below 10%, according to an estimate by the Centre for Global Development, based on new data published by the World Bank in April. Such progress nurtured hopes of more to come. Were the emerging world able to maintain a 4.5-percentage-point growth advantage over the rich world, then other things being equal its average income per person would converge with that in America in just over 30 years: scarcely a generation. Such a convergence would represent an historic change rivalled in its scope only by the extraordinary industrialisation that opened the global gaps between the rich and the rest in the first place, and completely unprecedented in its pace.

Alas, those hopes are now slipping away. An analysis of data on GDP per person which takes account of new estimates of living costs released in April by the World Bank’s International Comparison Programme (ICP) suggests that convergence has slowed down a lot.

Since 2008 growth rates across the emerging world have slipped back toward those in advanced economies. When the new ICP estimates are applied, the average GDP per head in the emerging world, measured on a purchasing-power-parity (PPP) basis, grew just 2.6 percentage points faster than American GDP in 2013. If China is excluded from the calculations the difference is just 1.1 percentage points. At that pace convergence with rich-economy incomes happens over a period of time more like a century than a generation. If China is included, emerging economies could expect to reach rich-world income levels, on average, in just over 50 years. If China is left out, catch-up takes 115 years.

The most recent 2014 growth projections from the IMF suggest the outlook is darkening further. They put the difference between the growth in emerging markets other than China and growth in the developed world at just 0.39 percentage points this year. That would put off full convergence for more than 300 years—indistinguishable from never as far as today’s societies are concerned.

It used to be harder

To get the rate of convergence back up to what it was a decade ago would seem as great an economic boon as the world could wish for. But the things which made that period exceptional cannot be replicated easily, if at all. From now on simply keeping up with the rich world will prove a challenge for many. Gaining ground will require reforms that look less achievable by the day. The great expectations raised over the last half-generation look increasingly likely to be dashed.

In 1997, just before the great catch-up got into its swing, the World Bank’s senior economist, Lant Pritchett, described a widening income gap between rich and poor countries as “the dominant feature of modern economic history”. Its dominance was rendered particularly galling by the fact that orthodox economics struggled to explain it. Theories of economic growth like the one published by Nobel-winner Robert Solow in 1956 predicted that, over time, poor economies should catch up with rich ones.

In the Solow model economies were poor because their workers had access to less capital. This capital shortfall implied that the return on investment should be high, so capital should flow from rich countries to poor ones, leading the two worlds to converge on similar levels of productivity and income. The fact that the richer countries would themselves grow while this was going on complicated matters, but not too terribly. Their long-run growth, Mr Solow reckoned, was driven by new technology which, once developed, could be adopted by poorer economies too. Indeed, the poor could potentially learn from the missteps made by the rich, and leapfrog directly to more productive ways of doing things.

The model seemed to apply well enough to the histories of then-rich countries. Thanks to its trailblazing industrial revolution, British GDP per person soared above that in other countries in the 19th century. By 1870 Britons were 30% more productive than Americans and 70% more productive than Germans. Yet this advantage disappeared as rivals improved upon Britain’s successes. By the early 20th century America had already surpassed Britain; not long after the second world war most of western Europe had caught up.

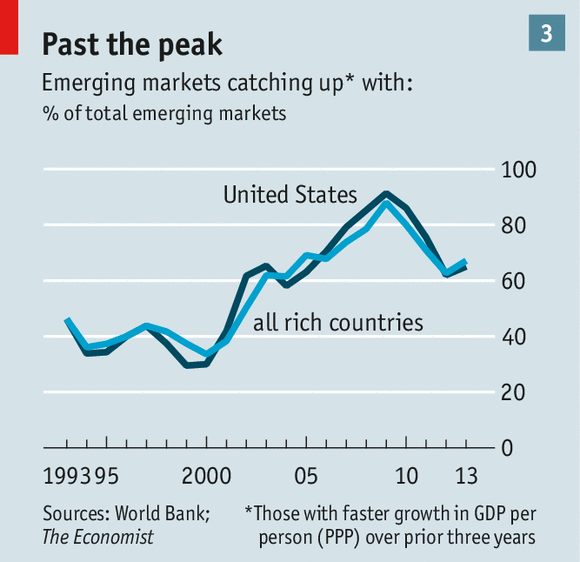

But what was true for Europe and the colonies it had created in temperate climes did not apply elsewhere. Prior to the late 1990s poor countries growing faster than rich ones were rare, and doing it persistently was rarer still. From the mid-1940s to the mid-1990s less than a third of developing economies were growing faster than the rich world at any one time. In any given economy one decade’s gains were often reversed in the next.

Some Asian economies proved to be exceptions. Japan, already industrialised in the first part of the 20th century, grew to be the world’s second largest economy. South Korea, Taiwan and a smattering of city-states like Singapore and Hong Kong also got rich. But promising bursts of growth in Africa and the Middle East in the 1960s and 1970s petered out. Crises repeatedly punctured bubbles of enthusiasm in Latin America. This dismal performance left dismal scientists feeling appropriately dismal. Writing in 1987 another Nobelist, Robert Lucas, noted: “The consequences for human welfare involved in questions like [getting poor countries to grow faster than rich ones] are simply staggering: Once one starts to think about them, it is hard to think about anything else.”

Economists tweaked their models, deploying new notions such as that of human capital to try and explain the persistent divide. Perhaps, they reckoned, it was only economies with comparable levels of investment and worker skills that converged to similar incomes, a phenomenon dubbed “conditional convergence”. Other segments of the profession explored different possibilities. Some reckoned institutions were the key. In the tropics, European colonial powers tended to impose institutions distorted by the overriding interest in extracting natural resources to which the interests and rights of the general population were secondary. Since these institutions were persistent, the legacy of past misgovernment continued to hold down incomes. Still other economists focused on geography and climate. Remoteness from economic centres and hot, disease-prone conditions could retard development.

Even as these debates continued, the world shifted beneath economists’ feet as growth in the developing world shot up from the end of the 1990s. A great deal of this was due to the rise of China as a manufacturing superpower, but that was far from being the whole story. In 2006, before the effects of the financial crisis slowed rich-country growth, emerging economies were achieving catch-up rates of more than five percentage points even if China was taken out of the mix. The catch-up experience was far more broad-based than it had been in previous growth spurts.

That is not to say the benefits were evenly spread (see chart 2). In eastern Europe and East Asia economies closed the gap at a remarkable clip, though for many eastern European countries a significant part of that growth simply reversed the contraction that followed the fall of the Soviet Union. In 1998 GDP per person in Poland was just 28% of that in America, while China’s was just 7%. By 2013 those figures had risen to 44% and 22%, respectively. Other countries made less progress. Brazil’s GDP per head was already 25% of America’s in 1998 and scraped forward just three percentage points over the next 15 years. For very poor countries even quite high growth provided little catch-up; in Ethiopia, GDP per head rose from 1.3% of that in America to 2.5%. Venezuela and Zimbabwe fell further behind.

A perfect lack of storms

The quality of governance and the introduction of market reforms deserves much of the credit for better performance in some countries than in others. But that pattern is superimposed on the effects of a confluence of helpful tailwinds.

One of these was a benign macroeconomic environment; in the 2000s interest rates were low and capital flowed freely. Another was rapid growth in commodity prices; many emerging economies rely heavily on natural resource exports. But the biggest push—which was not unrelated to the commodity-price boom—came from global trade. From 1980 to 1993 global trade grew at about 4.7% per year on average, or a bit more than the 3% rate of global growth. Between 1994 and 2007, however, trade grew at almost twice the rate that the world economy did. Goods exports soared to about a quarter of global GDP.

The lion’s share of this growth was due to China. During this phase of what Arvind Subramanian and Martin Kessler, of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, call “hyperglobalisation”, China’s trade became so important that it was critical not just to its own economy but to that of the world as a whole. The only previous economy of which that could be said was 19th-century Britain’s. But trade went up across the board, too.

Two broad factors drove that change. Years of trade liberalisation culminated in the establishment of the World Trade Organisation in 1995, with China acceding to it in 2001. At the same time technological improvements made possible longer and more complex supply chains. By the 1990s container shipping had made transporting goods around the world easier and cheaper than ever before, and the new ports needed to add trade capacity could be built quickly and easily. Better communications, and the development of computer-based design technologies that allowed precise details of components to be easily sent from place to place, and to be changed on the fly, mean that the range of things to be shipped increased. Cheaper and easier international trade allowed supply chains that had been segregated within countries and regions to expand across the globe.

This allowed for a much faster pace of catch-up. Where Japan and South Korea needed to build industrial and technological capabilities from the ground up, more recent sprinters needed little more than a supply of cheap labour and the regulations and infrastructure required to move products quickly in and out of factory towns.

The things manufacturing can’t make

Since the peak of the convergence era in 2008 these tailwinds have flagged—a becalming that can be seen in the number of developing countries catching up with rich ones, which has fallen sharply (see chart 3). Chinese growth has dropped from a peak of above 14% in 2007 to just over 7% now, and this has had a knock-on effect on commodity prices. Capital flows have become more fickle over the past year as rich-world central banks reduced their interventions in the economy. Trade, which tumbled in the global financial crisis, briefly roared back in 2010 but has barely kept pace with output growth for the past couple of years.

There are also fears that rapid catch-up might have meant shallow catch-up of a sort that could never be sustained. The factors that made industrial capacity easy to build did not encourage the development of the physical infrastructure and the capacity for things like design and marketing which, when they grow up alongside manufacturing, help to anchor it in the broader economy. China and some other emerging markets used the heady catch-up years to develop underlying technological and managerial capabilities and invest in infrastructure. Others made less progress.

Growth driven entirely by manufacturing brings particular worries. Dani Rodrik of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton points out that, over time, the share of employment in industry at any given stage of a country’s development has declined; middle-income economies today employ fewer people in manufacturing than did middle-income economies in the 1960s or 1980s. And the income level at which an economy typically enjoys the peak share of employment in industry has fallen by almost half.

While the manufacturing sectors of developing economies can quite often come to match the labour productivity of rich-world economies, the distance towards rich-world levels of wealth that an economy can travel simply by developing its manufacturing has been falling. With manufacturing as a proportion of the total economy peaking earlier and at a lower level, emerging economies can now find their catch-up more likely to stall at disappointingly low levels of income.

The last wave of convergence may also have come close to exhausting the potential created by reform-minded and capable governments. The labour-intensity of manufacturing in India has fallen over time, despite its rock-bottom labour costs, according to an analysis from the International Growth Centre, a think-tank. That may reflect in part the continued constraints of strict labour laws, which undermine the competitive advantages of low wages. Many of the economies that benefited least from the most recent convergence wave are economic “hard cases”, where infrastructure is least developed, government is most corrupt, and basic security is a constant concern.

Difficult, again

There could be ways forward for those willing to take them. A new round of global trade liberalisation focused on services could touch off a new wave of globalisation. As industrial employment declines in importance around the world, development increasingly means shifting workers from agriculture into urban service occupations. Expanding the range of services easily traded across borders could enable more developing-economy workers to participate in sectors with rising levels of productivity and wages. But trade in services remains highly restricted. A club of mostly rich countries has made efforts to negotiate a Trade in Services Agreement to update an accord reached in 1995. But there has been little progress.

Efforts to simplify global trade regulations and invest in infrastructure in the world’s poorest economies could also reduce barriers to participation in global trade in places like sub-Saharan Africa. Such measures were a necessary component of the “trade facilitation” agreement negotiated within the World Trade Organisation last year. Yet that agreement is also foundering thanks to Indian opposition to agricultural rules included in the deal.

No such efforts look likely to yield anything like the commodities boom and hyperglobalisation of the turn of the century. In the absence of such stimuli, history suggests that catch-up will be a long, difficult grind, built on slow improvement in institutions and worker skill levels. The past 15 years have changed perceptions regarding just what is possible. But they also deceived people into thinking broad convergence is the natural way of things. It looks like the world is now being reminded that catching up is hard to do.