Volatility returns to financial markets

The consensus is often caught out. If 2013 was a year when the pace of the stockmarket rally caught investors by surprise, 2014 was a year in which bond-market bears were dumbfounded. Yields fell, with those in Europe even becoming negative for bonds with two-year maturities. People were willing to make a loss to lend money to the French and Irish governments.

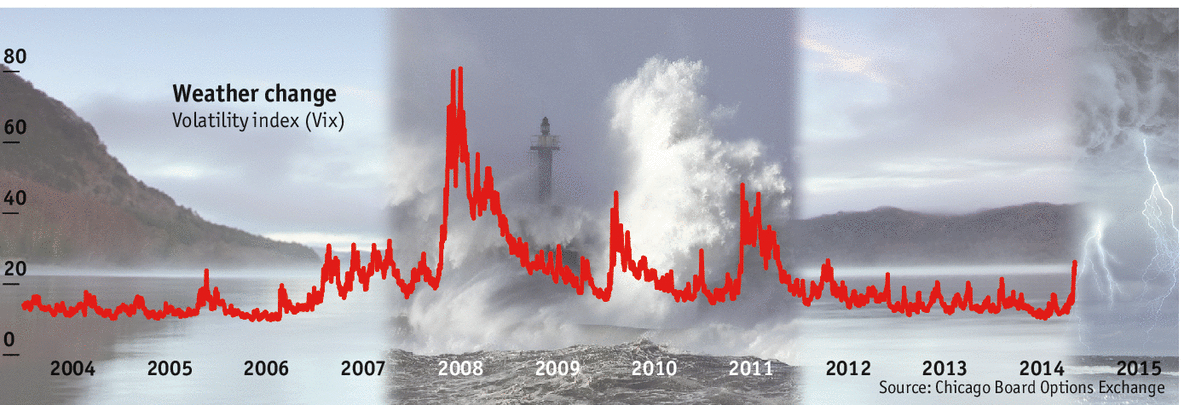

So what will be the surprise of 2015? Out of a wide range of candidates, the most intriguing would be the return of volatility. The most popular measure of volatility is the Vix, which focuses on the stockmarket (it measures the cost of options: in effect, the price investors are willing to pay to insure against sharp market moves). As the chart above shows, the 2008 economic crisis looks a bit like a sudden storm sweeping across a pond; there were two smaller subsequent squalls but all eventually became calm again. By the end of September 2014, the Vix was very low by historical standards.

That was probably the result of monetary policy; there has been no interest-rate rise in the big rich economies for several years and central banks have done much to calm the markets via asset purchases and bank lending. But that may change in 2015. The Federal Reserve has already stopped its bond purchases and there will be a lot of debate over the timing of the next rate rise—and over whether the Fed or the Bank of England will be the first to tighten policy. When markets see one rate increase, they tend to anticipate several more.

True, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan may keep their feet on the monetary accelerator for a while longer. But the policy divergence may cause volatility to show up in one particular place: the currency markets. After rising sharply in the midst of the crisis (Treasury bonds were seen as a safe asset) and then declining again, the dollar has been remarkably stable in the past two years. One of the most popular plays in the foreign-exchange markets is the “carry trade”, which involves buying the currency with the highest yield, selling (or borrowing) a currency with a low yield, and pocketing the difference. But in recent years, there has been precious little yield differential for traders to exploit. But there were signs in the autumn of 2014 that the dollar might be beginning a new bull run. The gap between ten-year bond yields in Germany and those in America was as wide as it has been since the introduction of the euro. There is now some “carry” to play with.

Another potential source of volatility is the stockmarket. There was a big wobble in October 2014 as investors worried about the lack of global growth and the potential for deflation. Bears have long predicted that the withdrawal of central-bank support will cause overvalued equities to slump, particularly on Wall Street; bulls say that a pick-up in global growth will allow the rally, which began back in 2009, to continue. They point to the strength of corporate profits, above all in America, and predict that they will rise even farther in 2015.

Conditions now seem reminiscent of the mid-1980s or the late 1990s, when investor enthusiasm for equities reached its height, resulting in a wave of merger activity and new companies floating on the market. When this happens, the stockmarket can jump sharply as new money is sucked in, and then collapse even more quickly as the smart money takes profits. If a collapse does happen, central banks may face a tricky decision: do they rescue the markets and reinforce the perception that they exist to prop up asset values, or do they let the markets fall and risk contagion in the financial sector and the hit to consumer confidence that might ensue?

Bond markets are also a potential source of turmoil. The ultra-low yields seen in Europe seem predicated on the continuance of Japanese-style conditions of sluggish growth and minimal inflation. Indeed, with the exception of Japan, buying bonds with yields this low has historically been a bad deal. There is little sign of inflation emerging for now. But if the economic conditions to justify such yields persist, voters will become even less happy than before and that may undermine belief in the European project. This may be particularly the case in France and Italy, where growth has been very weak. Anti-eu parties did well in the European Parliament elections in 2014; mainstream politicians may find it hard to ignore these views if stagnation continues.

In America, ten-year Treasury-bond yields of around 2% sit oddly with the equity bulls’ view that the economy is forging ahead at 1990s-style growth rates. One of the markets must surely be proved wrong. That tension could be the key financial issue of 2015.

Philip Coggan: Buttonwood columnist, The Economist