Multinationals will face rising labour costs

In 2015 the chief executives of big multinationals will worry a lot about pay: not their own, but that of their toiling staff. Rising labour costs will squeeze profit margins, which are at peak levels. Bosses will have to decide whether to resist or accommodate this pressure. Plenty, in the end, will raise their workers’ pay.

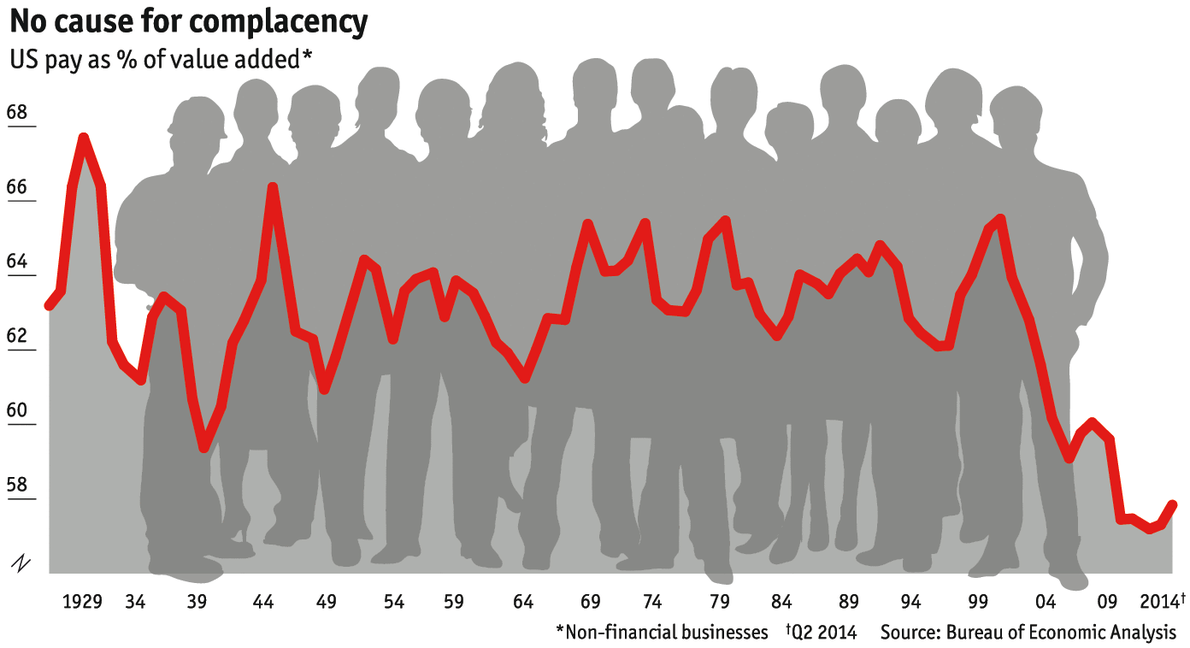

At first glance this may seem far-fetched. Since the 1990s Western firms have managed to restrain wages at home and boost efficiency. The share of value added by American non-financial firms that is spent on pay is 58%, its lowest since records began in 1929. Production has also been shifted overseas. American multinationals now have a third of their staff abroad. Per dollar of sales they are paid 40% less than their American colleagues. European firms are even more international.

Within big firms the struggle between capital and labour has turned into a rout. Relatively low pay costs have fuelled stockmarkets to all-time highs. Whereas bosses and investors in the 1970s obsessed about strikes and pay-bargaining, their counterparts today rarely view labour costs as a big issue for firms or the stockmarket. The annual regulatory filings of Walmart, one of the world’s biggest employers, contain 31 pages detailing the complex compensation of its executives, but do not mention how much it pays its 2.2m staff.

Yet while it is often ignored by firms, pay has not disappeared as a strategic issue. A 10% rise in wage costs would cut the typical multinational’s profits by 8%. Plenty of the big global firms that publicly reveal their labour costs saw them rise faster than sales in 2013, including Samsung, Unilever, Siemens, Nestlé and BMW.

This squeeze will intensify for three reasons. First, as Western economies climb slowly out of the slump, labour markets will tighten. The Federal Reserve thinks that unemployment will finally fall to normal levels by 2016. The Bank of England expects earnings to pick up strongly by 2015, and the European Central Bank expects them to pick up slightly by 2016.

Second, political concerns about inequality will lead to policies that force firms to pay their staff more. Barack Obama wants a higher minimum wage, as does Ed Miliband, the leader of the opposition Labour Party in Britain. In America the National Labour Relations Board, a regulatory body, plans to tighten the rules for contract workers who are the backbone of firms such as Federal Express and McDonald’s. Few private-sector workers are still members of unions, but those who are may feel emboldened, particularly if they control bottlenecks. In 2014 there were strikes at Los Angeles’s port, Canada’s mines and very nearly by stage hands at the New York Opera.

Lastly, labour costs in the emerging world are rising. This is important, given that the typical multinational now has 20-30% of its operations in the developing world, double the level in the mid-1990s. According to China’s current five-year plan, the average official minimum wage will rise by 13% a year. Partly as a result a slow shift in production is taking place away from China’s coastal regions, the workshop of the world. There is also a push to improve working conditions in poor countries after the collapse of a Bangladeshi factory in 2013 that killed more than 1,000 people. Those Western firms most exposed to Asian labour costs are already feeling the pinch. In 2014 Hennes & Mauritz, the world’s second-biggest fashion chain, said its margins would fall because it was unable to raise prices as fast as wages.

Salarymen of the world, unite

Businesses faced with rising labour costs will have two options. Those with large manufacturing operations can try to shift production to even cheaper countries. But finding places that have low wages, pliant workers and political stability is harder than it seems. Vietnam, supposedly the new mecca of manufacturing, had a wave of strikes in 2011-12. India is keen to attract more foreign factories but still suffers from its notorious red tape and corruption. Kenya, where some companies are scouting, has experienced terrorist attacks.

Firms with less mobile labour forces will try to boost productivity growth in the rich world, which has lagged in recent years. They will automate activities and use more robots: abb, a European engineering giant that has already sold a quarter of a million industrial robots, predicts a further “massive” boom in demand. Google and Amazon are testing delivery drones. Yet much of this technology is at an early stage. Some firms will increase their spending on training, to improve the skills of existing workers and the supply of new ones, but that will take time to have an impact, too. There will be more effort to reduce turnover among employees.

Despite all these efforts, many bosses will have no choice but to pay their staff a modestly greater slice of the value their firms create. That will not herald a major reduction in inequality, but it will be enough to squeeze margins and upset investors. For bosses writing bigger cheques, there will be one fringe benefit. For the first time in a decade, in 2015 the attention will be on other people’s pay packets.

Patrick Foulis: New York bureau chief, The Economist