Fabrizia Mancini, a mother of three, had to double her hours at work after her husband’s struggling employer stopped paying him in June. Massimo Berruti/AgenceVU for The Wall Street Journal

ROME—Like many Italian women, Anna Durante gave up full-time work outside the home after her first daughter was born more than a decade ago, leaving the role of family breadwinner to her husband.

But when he lost his job in a barber shop two years ago, Ms. Durante, then with two daughters, dusted off her diploma in elderly care and started looking for permanent work again.

The 30-year-old was finally hired last year by a cooperative providing aid for disabled people in Casoria, near Naples, while her husband remains unemployed.

“For my daughters I am both mom and dad. I do it all,” she says.

The harsh recession that followed the 2007-08 global financial crisis swept away many of the blue-collar jobs traditionally filled by men in Italy, the U.S. and other countries as well—a development that became known as “mancession.”

But the trend is having a surprising side effect in Italy: Not only were women more likely to keep their jobs, but tens of thousands more are heading back into the workplace. That could give Italy, which has one of the lowest rates of female employment in the West, an economic boost in the long run.

“At the beginning our world went upside down,” says Isabella Esposito, a 35-year-old mother of two from Naples. After her husband lost his job as a security guard, she went back to work as a beautician. “At that point, I had no other option left.”

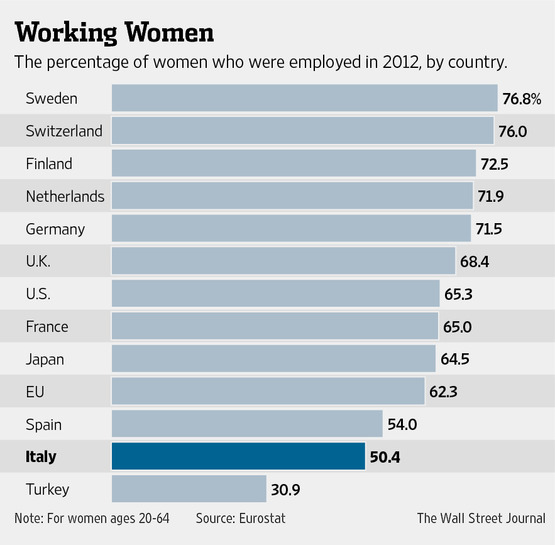

Only about half of Italian women are in the workforce, compared with an European Unionaverage of 62%, according to Eurostat. In Sweden the rate is 76.8% and in Germany, 71.5%.

Traditional attitudes help explain the difference. In Italy, the dominant cultural model—particularly in the south—still depicts women as stay-at-home wives and mothers more than breadwinners.

Widespread discrimination in the workplace, contributing to a dearth of women in positions of corporate or political power, has also been a powerful deterrent. For instance, nearly 9% of Italian working mothers say they have been fired from a job because of a pregnancy.

At one time, employers often forced a new female hire to pre-sign a resignation letter that would be put into effect if she got pregnant. The practice was outlawed in 2012.

Italian women also get less support in juggling work and home. They do 3.7 hours more household work a day than men, compared with an average of 2.3 hours among the 34 developed countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. About 24% of children under the age of three attend day care in Italy, compared with 33% in OECD countries.

Now, Italy’s protracted economic downturn is starting to push women into the workplace, even as traditionally male-dominated jobs disappear.

In the last five years, employment in manufacturing dropped by 7.5%, while construction jobs fell by nearly 19%. Italy’s overall unemployment rate has risen to 12% from 7.8% in 2009.

Yet the number of Italian women employed grew by 110,000 in 2012 from a year earlier, according to the statistical agency Istat. Last year, 8.4% of women were the primary breadwinner for married couples with children, up from 5% in 2008.

“The crisis started a sort of involuntary revolution in the Italian labor market, a shift that could end up changing the family dynamics and women’s bargaining power inside it,” said Magda Bianco, a senior economist specialized on gender issues at the Bank of Italy.

The rise in employment is concentrated in areas such as the civil service, health care and family services—sectors that have proved more recession-resistant—as well as in low-skill areas, such as cleaning services.

When furniture retailer IKEA advertised 200 new positions for a new store in Pisa in August, about two-thirds of the 29,000 applicants were women.

Last year, the government headed by Mario Monti sought to encourage women to go to work by introducing vouchers granting working mothers a monthly contribution for child care as an alternative to parental leave.

Moreover, with Italy raising progressively the retirement age for women from 62 in 2012 to 66 in 2018, the number of over-50 workers is also increasing.

Another sign of pent-up demand by women for jobs is the rise in part-time workers saying they would prefer full-time jobs.

About one-third of Italian working women are part-time—traditionally viewed as a way to juggle work and family—compared with an OECD average of 24%. But since the onset of the crisis, the percentage who say they would prefer full-time work has nearly doubled, to 14.1% last year from 7.7% in 2007.

Fabrizia Mancini, a 39-year-old mother of three in Rome, went back to work part-time at an advertising agency about two years ago, a year after her youngest was born. But in June she had to almost double her hours when her husband’s troubled company stopped paying his salary.

“I can’t afford going home early now, I need to work as much as I can,” she says.

The upper echelons of corporate Italy are also cracking open the door. In 2011 the share of women on boards of listed companies stood at around 6%, less than half the EU average of 14%.

Last year, the government introduced a quota requiring that one third of boards of listed companies and state-owned companies be made up of women by 2015, that has already pushed the number up to 17%.

Economists agree that getting more women into the labor market would help counterbalance the effects of a shrinking working-age population, thus reducing the strain on public welfare and raising competitiveness.

The OECD calculates that if female participation rates in Italy converged to those of men by 2030, the Italian labor force would increase by 7% and per capita gross domestic product would grow by one percentage point a year for the next 20 years.

“We need to transform what is now a serious weakness into an extraordinary opportunity, which could give a strong boost to Italy’s economic and civil growth,” said Bank of Italy Governor Ignazio Visco in a speech last year.

But obstacles remain. For instance, with youth unemployment at around 40%, younger women report having an even harder time entering the workforce than men.

And given the meager state support available for working mothers in Italy, the recent push to raise the retirement age could make it harder for women with small children to work because they often depend on retired parents to fill the gaps in child care.

“It’s too early to say if this is a turning point,” Ms. Bianco says.

Write to Giada Zampano at giada.zampano@wsj.com