By: Jacob Bunge

Source: The Wall Street Journal

One of the signature events of American capitalism, the opening-bell ceremony at the U.S.’s biggest stock exchanges, has long been held on Wall Street—or, more recently, in the glittering canyons of Times Square.

But it is possible that the U.S.’s biggest stock-market, as measured by volume, will soon ring in the trading day from a two-story office building beside a freeway in suburban Kansas City.

The shift reflects the changing nature of U.S. stock trading and the upstart firm that is upending the market’s decades-old pecking order.

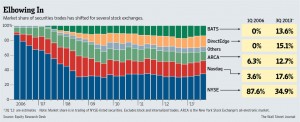

BATS Global Markets Inc., based in Lenexa, Kan., last month announced an all-stock deal to merge with smaller U.S. rival Direct Edge Holdings LLC, based in Jersey City, N.J. The deal, terms of which weren’t disclosed, would toppleNasdaq OMX Group Inc. NDAQ -0.97%as the second-largest U.S. exchange operator in terms of trading activity, and last week the volume at BATS and Direct Edge combined to virtually match that of the country’s biggest market operator, NYSE Euronext NYX +0.01% .

Adding Direct Edge’s two U.S. exchanges to BATS’ s own pair would give BATS one-fifth of the U.S. market, a bigger pool of liquidity that officials believe will give the company a leg up in the competition to capture trades and sell pricing data to traders.

Founded only eight years ago, BATS is a mere toddler compared with the NYSE, which traces its roots to 1792 and was formally founded in 1817, and Nasdaq, which was created in 1971. But BATS’s embrace of automated trading allowed it to set up home base thousands of miles from Manhattan and save millions of dollars in expenses.

The actual buying and selling on BATS’s exchanges happen on trade-matching systems within a high-tech data facility center in Weehawken, N.J., near servers used by banks, trading firms and rival exchanges.

“They could be based in Fargo, N.D., and it wouldn’t matter,” said Justin Schack, managing director with brokerage firm Rosenblatt Securities Inc., which trades on BATS’s markets.

The company isn’t immune to the pitfalls of technology: BATS suffered an embarrassing episode last year when an internal software glitch forced it to cancel its own initial public offering. And on Thursday, network problems shut down BATS’s smaller U.S. stock exchange for nearly three hours.

BATS retains a midwestern sensibility, in large part reflecting Chief ExecutiveJoe Ratterman, a Kansas City-area native who has never worked at a Wall Street firm.

Polo shirts are more common than suits in the company’s leased offices, where a 50-pound bell next to the central stairwell kicks off trading, a far cry from the brass bell situated on the NYSE podium and the touch-screen button that starts Nasdaq’s trading day in Times Square. Among the recent BATS ringers: local grade-school students and the Kansas City Chiefs’ furry, gray mascot, K.C. Wolf.

BATS will keep its headquarters in Lenexa following its planned merger with Direct Edge, aiming to keep expenses low. The company built its original trading platform for less than $10 million and and reported $118 million in operating expenses for 2012, according to a spokesman, versus NYSE’s $1.7 billion that same year and Nasdaq’s $973 million.

But after completing its merger with Direct Edge, the enlarged BATS may stake out an enlarged Manhattan office, which could help raise the exchange group’s profile with prospective issuers. A BATS spokesman said the company hasn’t yet determined whether its combined New York-area offices will be in Manhattan, Jersey City or elsewhere.

A bigger New York City presence could help BATS compete for listings, as the stamp of Wall Street approval and the bell-ringing publicity help justify five- and six-figure fees to list shares on the NYSE and Nasdaq.

BATS will face stiff competition going up against the NYSE, for centuries known as the home for American blue-chip stocks, and Nasdaq, which courted IPOs for decades to earn its reputation as the exchange for technology listings.

The listings game is “a brand exercise,” according to David Weild, chief executive of capital-markets software firm IssuWorks Holdings LLC and a former Nasdaq vice chairman who oversaw listings.

NYSE Euronext, the NYSE parent, itself is close to finalizing a deal to be bought by IntercontinentalExchange Inc.,ICE +0.17% a commodity-market operator based in Atlanta that runs futures exchanges in London and Chicago. The NYSE will retain its iconic downtown Manhattan floor in that deal.

Representatives for Nasdaq and NYSE declined to comment.

Listings are a big business for exchanges, which measure success and fees by the prestige of landing big-ticket stock offerings. NYSE last year pulled in $448 million in revenue from listings, representing 19% of the company’s overall revenue, subtracting transaction-based costs. Listings generated $224 million in revenue for Nasdaq OMX last year, about 13% of revenue, less transaction expenses.

BATS officials have previously seen a niche for the company’s low-cost, technology-centric approach in listings, particularly when it comes to exchange-traded funds and small-cap companies. Early last year, BATS laid out a listings strategy that would charge companies lower fees than are charged at NYSE and Nasdaq, while paying incentives to traders for more-competitive prices in BATS-listed securities. Since January 2012, exchange-traded fund issuers iShares, a unit of BlackRock Inc.,BLK -0.40% and ProShares have listed 20 products on BATS’s main exchange. BATS launched a new bond-focused ETF from iShares on its exchange Thursday.

Plans to draw corporate listings floundered in March 2012, however, after a software bug forced BATS to pull its own initial public offering. Mr. Ratterman issued a public apology and ceded chairmanship of the company to Paul Atkins, a former commissioner at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

BATS has said it has no plans to relaunch its IPO.

The merger with Direct Edge could provide fresh momentum to the listings effort, however.

Through the deal, “things I previously would’ve thought of as impossible become possible,” including a new approach to landing corporate listings, said Direct Edge Chief Executive William O’Brien in an interview. A spokesman for BATS said the company will weigh its listings strategy after closing the deal with Direct Edge, expected in the first half of next year.

BATS has extended its reach with 164 employees, less than a tenth of the staff of its larger rivals. BATS and Direct Edge together employ about 300 people.

Reference: Bunge., J. (2013, Sept. 27).BATS prepare to take on big bell ringers. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303983904579095793544399518.html?mod=rss_whats_news_us